Water forms the foundation of all natural systems. Its unique physical properties make it irreplaceable for energy transfer and ecosystem regulation—earning it the designation as “the bloodstream of the biosphere.” Beyond its ecological role, water is essential for human health and economic prosperity.

To secure reliable access to this vital resource, humanity has developed infrastructure with three core functions: storage, transport, and treatment. Water infrastructure is characteristically capital-intensive and long-lived, with high upfront costs that cannot be easily recovered if projects fail. In Europe, the Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC makes a distinction between services and uses.

- Water services provide drinking water and wastewater treatment facilities and are tied to the principle of cost recovery water uses. This includes including environmental and resource costs

- Water uses encompass a wide range of human activities (energy, agriculture, industry, inland navigation, … Usually the infrastructure is funded by the sector itself according to its own rules. According to the polluters-pay principle, water uses are due to contribute in an “adequate” manner to the recovery of costs incumbent to water services providers (the so-called utilities). As it concerns the impacts of water uses on water resources, this is to be addressed via programs of measures based on a cost effectiveness analysis.

Today, the water sector is facing unprecedented challenges, including increasing pollution, escalating water scarcity (water needs are growing at twice the rate of population growth source UN Water) and intensifying climate impacts. In many OECD countries, infrastructure is ageing and technology is outdated, while governance systems are often ill-equipped to handle rising demand, environmental challenges, continued urbanisation, climate variability and water-related disasters. These pressures have elevated water from a niche concern to a strategic priority for governments, corporations, and institutional investors.

Globally, up to $7 trillion by 2030 must be mobilized for global water infrastructure, if the World is to meet the water-related SDG commitments and address decades of underinvestment (source: World bank).In 2020, the European Commission and OECD arrived to the conclusion that that if countries want to comply with the Drinking Water Directive and the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive and to enhance the efficiency of their water supply systems, the EU countries would need to allocate additional cumulative total expenditures of about €255 billion 142 for water supply and sanitation by 2030.

While the public sector will remain a pivotal investor, more capital from the private sector is necessary to close the infrastructure gap. However, developing pipelines of bankable projects is challenging. High development and transaction costs often prevent project preparation, and business funding models deliver inadequate risk-adjusted returns. Nevertheless, it is important to distinguish between water services and water uses.

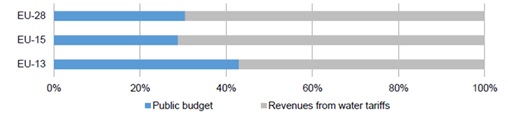

Water and sanitation services are generally sourced and provided locally. Consequently, investments are often relatively small-scale and fragmented. Furthermore, pricing services is a complex issue. A matrix of factors, including affordability, human rights, political expediency and social acceptance, often combine to make future inflows for water infrastructure assets less predictable than in other sectors. In most cases, utilities do not collect enough revenue through tariffs to cover operational and capital costs. The chart below illustrates the financing sources for water supply and sanitation services in the EU28, based on the average for the period 2011–2015 (source OECD / Eurostat).

Water uses encompass a wide variety of activities. These can include various types of infrastructure (such as conventional ‘grey’ solutions, nature-based solutions, or a combination of the two), as well as large, centralised infrastructures and small-scale, decentralised systems. This broad category may also encompass investments intended for other purposes that contribute to water management, such as green roofs or permeable surfaces that reduce rainwater runoff. Similarly, the range of financiers is diverse, with different mandates, investment objectives, risk appetites and liquidity needs. Additional classifiers for water investments include scale (from watershed to household), function (e.g. irrigation, energy, flood protection) and operating environment (e.g. ownership, governance and regulation). Water-related investments connect multiple sectors and policy agendas beyond the water sector, including agriculture, energy, urban development and public health, among others. The impacts of water-related risks can propagate through multiple channels and at different scales. In most cases, hydrological boundaries and administrative perimeters do not coincide. Risks are high and often accumulate in an amalgam that is poorly understood.

In this context, creating a sustainable and resilient water sector requires more than just increased capital investment. A challenge of this scale requires a commitment to reforming the sector through progressive policies, institutions and regulations, as well as better planning and management of the capital already allocated to it.. The priority issues to be addressed can be summarised as follows:

- Identifying additional sources of funding. The management of water resources provide a mix of public and private benefits, with many benefits (e.g. improved ecosystem functioning) that should be not easily quantified and monetised. Flood protection, for example, is spatially distributed and not associated with a specific revenue stream. On the other hand, it is also necessary to take into account significant indirect impacts on business activities, which are likely to happen through increases in price and availability of water or water-related intensive inputs in their value chains.

- Reduce information asymmetry between project developers and investor. There is a lack of appropriate analytical tools and data to assess complex water-related investments and to track records. It results in significant transactional costs. Sound investment planning for financing water-related investments is impeded by a robust projections on investment needs and the state of existing assets. Since investments in water security are often context specific, it is challenging to scale up financing models or to replicate lessons-learnt from previous projects.

- Setting up an regulatory framework: There is now an enhanced recognition that bottom-up and inclusive decision-making is key to effective water policies. However the concept of ‘Integrated Water Resources Management” still needs to be developed further to become fully operational. Special attention is to be given to inconsistency of water-related policies across sectors which impedes efficient cross-sector planning and capturing potential synergies. Irrigation is an interesting case in this respect since 40 % of global food production depends on irrigated agriculture, covering 20% of the world’s cultivated land.

- Risk management: Decisions regarding water infrastructure typically rely on engineering, modelling and planning that base projections of future needs on historical patterns of water availability and use. Emerging and systemic threats, including the impacts of climate change, intensify the challenge of financing water-related investments and underscore the value of flexible and robust approaches to financing long-lived capital intensive infrastructure. Incorporating resilience into water-related investments is needed to ensure that system-wide enhancements are made to help absorb and rebound from residual risks as well as events that may be difficult to predict.

Reading list

1) Water Europe, “Socio-economic study on the value of the EU investing in water”, September 2024 (link)

2) OECD, “Financing a Water Secure Future”, OECD Studies on Water, 2022 (link)

3) UN World Water Development Report 2020: Water and Climate Change (link)

4) World Bank, “Closing the $7 Trillion Gap: Three Lessons on Financing Water Investments from World Water Week”, post published on the water blog on September 16, 2024 (link)

5) World Water Council, “A typology of water infrastructure investors”, White paper, 2018 (link)