The environmental impact of cities

Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a proportion that is expected to increase to 68% by 2050. Projections show that urbanization – the gradual shift in residence of the human population from rural to urban areas, combined with the overall growth of the world’s population – could add another 2.5 billion people to urban areas by 2050, with close to 90% of this increase taking place in Asia and Africa.

Urbanization produces significant and complex environmental effects that are frequently distributed across different locations and time periods. These impacts often interact and reinforce one another, resulting in systemic environmental change. It can be concluded that urban areas tend to externalize environmental costs to remote ecosystems and future generations. The primary impacts include:

- Resource Consumption and Material Flows: Urban areas cover only about 3% of the Earth’s land surface but consume approximately 75% of global natural resources and energy.

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change: Urban areas generate approximately 70-75% of global CO2 emissions. The urban heat island effect amplifies these impacts locally. Cities typically run 1-7 °C warmer than surrounding rural areas

- Water System Disruption: Cities cover natural surfaces with impermeable materials, preventing water infiltration and increasing stormwater runoff while water abstraction depletes aquifers and diverts surface water, often creating water stress in surrounding regions.

- Waste Generation and Pollution:. Globally, cities produce over 2 billion tons of municipal solid waste annually. Much of this waste ends up in landfills or the natural environment. In particular, plastic pollution originating from cities has become a planetary-scale problem.

- Air Pollution and Atmospheric Impacts: Cities generate severe air quality problems associated with severe public health issues for the local population and long-range atmospheric deposit of pollutants

- .Biodiversity Loss and Habitat Fragmentation: Urban expansion directly destroys natural habitats through land conversion for buildings, infrastructure, and agriculture to support urban populations. Urban sprawl fragments remaining habitats into isolated patches too small to support viable populations of many species.

Cities as a hub for transitioning to Circular Economy

Cities play a pivotal role in the transition to a circular economy, serving as both testing grounds for circular principles and scaling platforms for widespread implementation. Their unique position stems from several key factors.

- Cities generate approximately 85% of the world’s GDP. Cities are recognized as powerful engines of economic growth, innovation, and productivity, attracting resources and talent that drive global economic activity.

- Urban environments offer the concentrated networks that facilitate effective collaboration among businesses, research institutions, and startups—an essential foundation for advancing circular innovation.

- Urban environments serve as ideal settings for advancing material loop closure. These areas are particularly well suited to implementing advanced material recovery systems and comprehensive waste-to-resource initiatives.

- Municipal governments possess significant regulatory power to shape circular practices through building codes, procurement policies, and waste management regulations.

- Cities influence consumption patterns through infrastructure design and cultural initiatives. The concentration of diverse populations in cities also accelerates the spread of new consumption models

Enabling capacities for cities to engage the transition

Prioritizing capacity development is vital for enabling agile circular economy transitions in urban environments. Establishing foundational capabilities lays the groundwork for all future initiatives. Successful agile circular economy transitions rely on a comprehensive transformation of municipal operations that reaches far beyond individual projects. By cultivating core capacities—particularly adaptive leadership and cross-departmental collaboration—cities ensure that investments in technical and specialized skills translate into tangible outcomes, effectively overcoming the limitations of conventional bureaucratic frameworks.

- Adaptive Leadership and Change Management: The most critical capacity to develop first is adaptive leadership throughout the municipal organization. This includes developing what urban scholars call “entrepreneurial governance” – the ability of public sector leaders to take calculated risks, learn from failures, and pivot strategies based on evidence rather than political convenience..

- Cross-Departmental Collaboration Infrastructure: there is a strong need for building organizational structures and processes that enable genuine cross-departmental collaboration. This means creating formal mechanisms like integrated project teams, shared performance metrics, and joint budget authorities that allow different departments to work together on circular economy initiatives without constantly navigating bureaucratic boundaries.

- Rapid Learning and Data Systems: Cities must develop robust systems for collecting, analyzing, and acting on real-time data about their circular economy experiments. This includes both technical infrastructure (sensors, data platforms, analytics tools) and human capacity (data scientists, evaluation specialists, rapid feedback processes). The ability to quickly measure what’s working and what isn’t is essential for agile iteration cycles.

- Community Engagement and Co-design Skills: Circular economy success ultimately depends on citizen behavior change and community acceptance. Therefore, cities need to develop what researchers call “civic technology” skills – the ability to engage diverse communities in rapid design and testing cycles without creating engagement fatigue or excluding less digitally connected populations.

Utilities as a key actor of the transition

Utilities have distinctive roles in city organization—such as managing network infrastructures, delivering indispensable services, functioning within natural monopolies, and upholding public interest responsibilities—position them as influential actors in both enabling and potentially constraining the adoption of circular practices.

- Utilities control the essential flows that make circular economy possible – water, energy, waste management, and increasingly digital connectivity. They operate the physical infrastructure that can either facilitate closed-loop systems or maintain linear resource consumption patterns.

- Modern utilities are evolving from service providers to resource recovery companies. Water utilities are extracting valuable materials from wastewater streams, energy utilities are developing systems to capture and redistribute waste heat, and waste management utilities are becoming material recovery specialists

- Utilities are essential for enabling the distributed, neighborhood-scale circular systems that are made available to cities thanks to new technologies. However, this requires utilities to move away from traditional centralized models toward more flexible, networked approaches that can accommodate multiple small-scale circular initiatives.

- Utilities control vast amounts of data about urban resource consumption patterns, which is essential for effective circular economy planning. Smart utility systems can provide real-time information about energy use, water consumption, and waste generation that enables both municipal planning and individual behavior change..

- Utilities represent enormous capital resources that could be redirected toward circular infrastructure, but their investment decisions are often constrained by regulatory requirements for lowest-cost options and traditional return-on-investment calculations that don’t account for circular economy benefits. However, when utilities can invest in circular infrastructure, they have the scale and technical expertise to implement solutions that smaller actors cannot achieve.

- Utilities have direct relationships with all urban residents and businesses, giving them unique capacity to influence consumption behaviors and support circular practices. Through pricing signals, information programs, and service design, utilities can encourage resource efficiency, peak demand management, and participation in circular initiatives like community solar or organic waste recovery programs.

Fostering agility and collaboration

Utilities are fundamentally designed for stability, not agility. Their core mandate is to provide reliable, uninterrupted service. Infrastructure projects typically operate on 20-50 year timeframes with detailed planning requirements, which conflicts fundamentally with the rapid iteration cycles that agile development requires. A utility cannot easily pivot its strategy when it has billions invested in centralized infrastructure designed for linear resource flows. This imperative creates organizational cultures that are deeply risk-averse and resistant to experimentation. In addition, Regulatory approval processes for rate changes, service modifications, or new programs can take months or years, making rapid experimentation nearly impossible

Most utilities operate under rate structures where revenue is tied directly to throughput – selling more electricity, water, or waste disposal services. This creates a fundamental conflict of interest: circular economy aims to minimize resource consumption, but utilities’ financial viability depends on maximizing it.

Utilities can typically only recover “prudent costs” for established services. Experimental programs or circular economy pilots often don’t fit neatly into existing cost categories, creating financial risks that utility executives must personally defend to regulators and shareholders. Failed experiments can be deemed “imprudent,” leaving utilities unable to recover their costs and executives vulnerable to shareholder lawsuits.

Performance measurement systems mandated by regulators focus almost entirely on traditional service metrics – reliability, water quality, emission compliance – with little recognition of Circular Economy contributions like resource recovery, waste reduction, or industrial symbiosis facilitation. This means utilities have no regulatory incentive, and often face regulatory barriers, to prioritizing circular initiatives.

Overcoming these structural barriers requires utilities to develop new organizational capacities that enable both agility and collaboration

- Experimental Infrastructure: Utilities need ability to create pilot programs and testing environments without disrupting core service delivery. This might include sandbox regulations, dedicated innovation budgets, or partnerships with municipalities for circular economy experiments.

- Flexible Service Models: Moving beyond one-size-fits-all service delivery toward customized solutions that can accommodate different circular business models and community needs. This requires both technical flexibility and regulatory adaptation.

- Stakeholder Collaboration: Utilities need to develop capacity to work collaboratively with municipalities, businesses, and communities rather than operating as isolated service providers. This includes participating in the cross-sector collaboration processes that circular economy initiatives require.

- Adaptive Planning: Traditional utility planning operates on long-term cycles that conflict with agile development approaches. Utilities need to develop planning processes that can accommodate rapid iteration while maintaining system reliability and safety.

- Performance Measurement: Utilities need new metrics and measurement systems that can track circular economy outcomes, not just traditional service delivery metrics. This includes measuring resource recovery, system efficiency, and contribution to circular business model development.

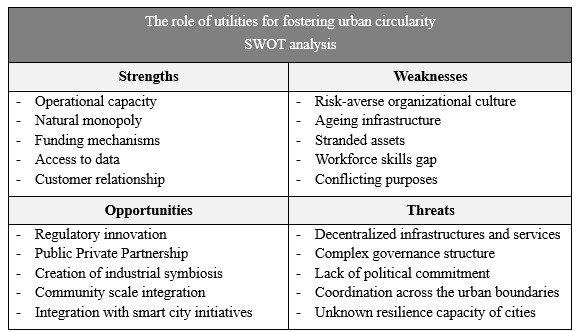

SWOT Analysis of the Utilities Sector Position

Understanding utilities’ strategic position requires honest assessment of their capabilities and constraints. While they possess unique infrastructure control and customer relationships, they also face fundamental structural barriers to circular transformation. The following SWOT analysis reveals both significant advantages and substantial challenges:

As conclusion: utilities face a fundamental paradox. They possess the infrastructure control, capital resources, and customer relationships essential for circular economy transitions, yet their organizational structures, regulatory frameworks, and business models were designed for precisely the opposite purpose—maximizing linear throughput. This is fundamentally a collective action problem requiring coordinated intervention from regulators, municipalities, utilities, communities, and financial institutions. No single actor can deliver this transformation alone, and each must engage at the same time in the organizational transformation needed to enable circular resource flows.

Reading list

- EIB, “The 15 Circular Steps for Cities”, 2024 (link)

- Reflow “white paper” Horizon 2020 project aimed at cocreating circular and regenerative resource flows in cities (link)

- United Nations Environment Programme, “Circular economy in cities – Key messages”, 2024 (link)

- Climate-KIC & Veolia, “Circular Cities: A Practical Approach to Develop a City Roadmap Focusing on Utilities”, 2019 (link)

- Anders Wijkman. 2021. Reflections on Governance for a Circular Economy. A GCF Report, 2021 (link)

- GIZ, “Shifting circular: urban infrastructure and policy changes towards renewed territorial metabolisms”, 2023 (link)