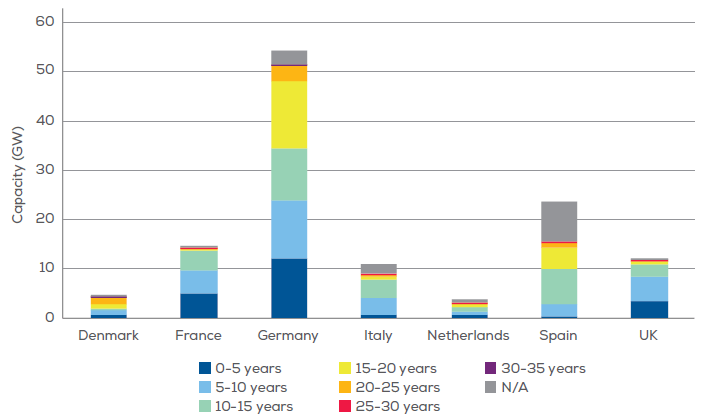

Today, the first generation of wind turbines is nearing the end of its operational life. This is a major challenge for the wind industry. On the one hand, the repowering of existing wind farms (often in the best locations) is becoming a major issue. According to Wind Europe (link), it can double the generating capacity (in MW) of a wind farm and triple the electricity output because the new turbines produce more power per unit of capacity. This is achieved by reducing the number of turbines by an average of 27%. However, operators have faced significant difficulties and delays in renewing their permits. Less than 10% of the wind turbines that will reach the end of their life in 2023 will be repowered. Many have just received a permit extension. On the other hand, the wind industry claims to be 100% circular. If composites can achieve an optimal balance of high strength-to-weight ratio, mechanical properties, design flexibility and durability, recycling these materials is a challenge whose magnitude is only beginning to be understood. According to Wind Europe, the total amount of decommissioned blade material in Europe will increase from less than 100,000 tons in 2020 to 350,000 tons in 2030. The chart below (source: Wind Europe paper) shows the age of Europe’s onshore wind fleet

It remains that circular economy strategies are higWind turbine blades are typically made of composite materials consisting of 60-70% fiber reinforcement (in 90% of cases glass fiber; carbon fiber offers greater strength and stiffness and is easier to recycle compared to glass fiber, but at a higher cost) embedded in a 30-40% polymer matrix (usually epoxy or polyester resin). Blades have a sandwich structure and metal wiring for lightning protection, and a thermoplastic coating to protect against UV and moisture. The standard design life is 20-25 years.

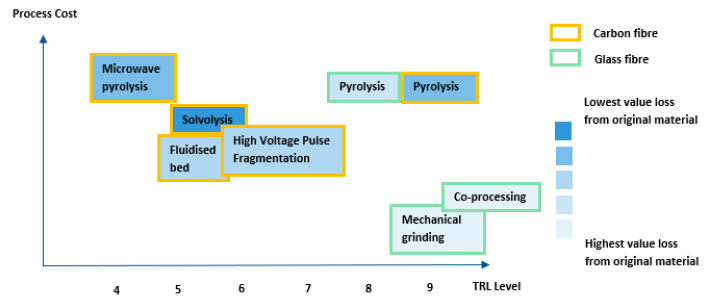

In Europe, landfill is not an option for the disposal of blade waste, nor is incineration, as fiberglass cannot be incinerated. In a few cases, blade materials can be repurposed as street furniture (bridges, bicycle shelters, etc.), but this remains at a demonstration level. Achieving 100% blade recycling remains the goal of the wind industry. The chart below (source: Wind Europe paper) shows the different recycling technologies that can be considered according to process cost and technology readiness level (TRL).

Among these recycling options, mechanical grinding, pyrolysis and cement co-processing are the most mature technologies, but they are not yet widely available or cost effective. DecomBlades (link) is an example of a project that aims to develop functional, sustainable value chains to manage end-of-life wind turbine blades from decommissioning to reprocessing and reuse in new applications. It will also establish disposal specifications to facilitate blade dismantling and recycling (see example of blade material passport documents from LM Wind Power, Vestas and Siemens Gamesa).

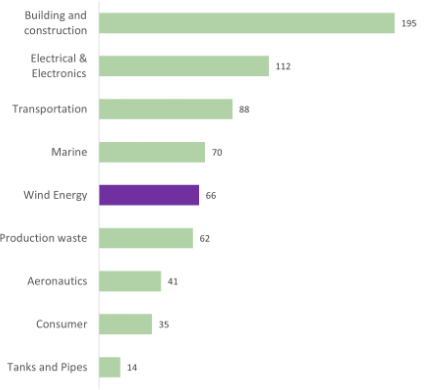

It should be noted that composite recycling is not just a challenge for the wind industry. The inherent properties of composites make them suitable for a range of medium to high value applications with a design life typically in excess of 5 years. Based on estimates from the European Composite Industry Association (link), the wind industry will contribute 66,000 tons of thermoset composite waste in 2025. This is only 10% of the total estimated thermoset composite waste. The chart below shows the other composite waste generating sectors in thousands of tons in 2025.

Composite recycling is therefore a cross-sectoral challenge that requires a lot of effort, investment and innovation to make the value chain circular. According to the CSR Europe (link) , it is estimated that 683,000 tons of composite waste will be generated in Europe in 2025, not including the already accumulated untreated waste. At the same time, the global recycling capacity is estimated to be less than 100,000 tons per year. The main issues to be addressed are:

- R&I funds should also be earmarked for the development of new high-performance materials with improved circularity (design for longer life, reuse/recycle and “from and for recycling” approach). With regard to windmill blades, the ZEBRA project (link) has developed new types of thermoplastic resin blades that offer the same mechanical performance as the thermoset materials used in current blades, but can be 100% recycled for the same use. Interesting progress is also being made with bio-based materials such as bamboo.

- Today, there is limited legislation governing the treatment of composite waste at both EU and national levels. In addition, existing national legislation is not necessarily aligned at the international level. The development of a harmonized regulatory framework and standards at EU level would likely be helpful for the development of a pan-European market for the recycling of composite wastes. As in many cases the recycled material cannot compete with the price of virgin materials, particular attention should be paid to the use of the right economic incentives. This is critical due to high investment and energy costs.

- Logistical and technological solutions for disassembly, collection, transport, waste management and re-integration into the value chain need to be implemented across Europe in order to diversify and scale up composite recycling technologies. To this end, it would be helpful to revise the European Waste Catalogue to create specific waste codes for end-of-life composites from decommissioned equipment.

- There is a need to promote the principles of discoverable, accessible, interoperable and reusable data and digital assets to get a clear view on the life cycle of composite materials . One contribution to the way forward is the application of a Digital Product Passport for the composites sector.