The Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC (link) was adopted in 2000 after a12-yearof negotiation. The ambition was to restore the good ecological quality by 2015. Compared to previous EU Directives which deal with punctual issues (drinking water, bathing water, hazardous substances, etc. ) or specific pollution (urban waste water, nitrates), the WFD was clearly a big change since it provided an integrated water management approach at river basin level. This was coupled with other advanced features such as

- Objective driven legislation

- Ecological quality as a mean of integration

- Adaptive planning capacity (6 year cycle)

- Economic instruments to support decision-making and to influence polluters’ behavior

- Transboundary cooperation (60% of the EU surface area lies in river basins that cross at least one national border)

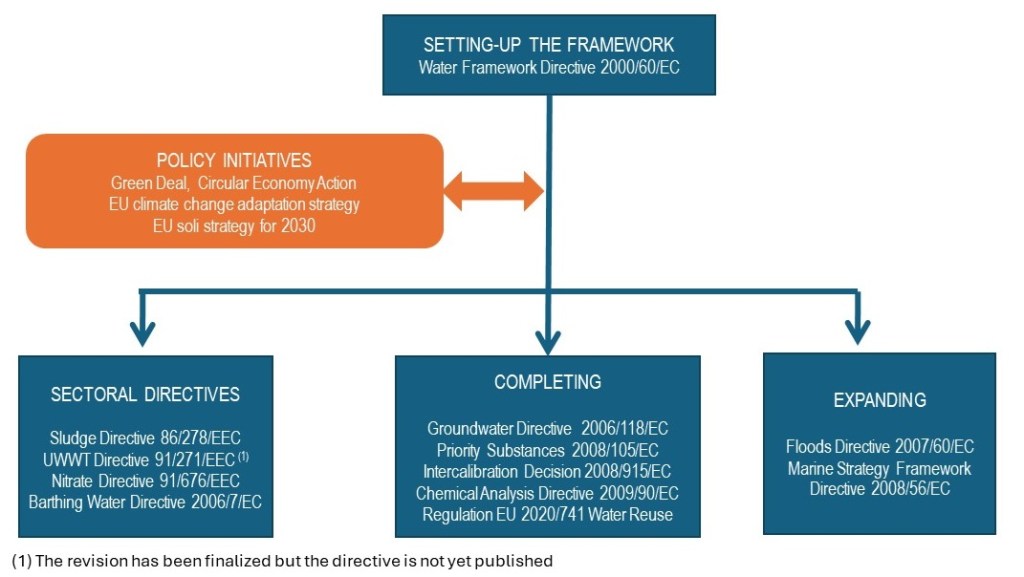

As illustrated by the picture above, the WFD has provided a comprehensive management framework for fresh and coastal waters. The WDF has been coordinated with the previous sectoral directives and further detailed in daughter directives (groundwater, environmental quality standards). The flood and marine strategy directives were adopted to complete this framework while Climate Change is an issue of ever growing importance . The chart below shows how the water legation is today articulated.

In 2019, the European Commission conducted a fitness check (link) under Article 19(2) of the Water Framework Directive, which requires the Commission to review the WFD and its daughter directives no later than 19 years after their entry into force and to propose any necessary amendments. The Fitness Check concluded that the assessed Directives are fit for purpose, but also highlighted some recurring implementation difficulties.

- Governance: Many of the pressures on water are site-specific. In line with the principle of subsidiarity, Member States have considerable discretion in identifying site-specific measures to reduce pressures on water. In practice, the integration of WFD objectives with other sectors (biodiversity, agriculture, inland navigation, energy, etc.) has proven to be highly problematic in many cases. The participatory planning process at the river basin level is often insufficient to achieve real community buy-in for the measures to be implemented.

- Funding needs: There was no systematic impact assessment of new legislation when it was adopted in 2000. It was wrongly assumed that better coordination at river basin level would be sufficient to achieve good ecological status. According to the 6th WFD Implementation Report – COM(2021) 970, the total investment cost of measures planned in the 2nd WFD planning cycle (2016-2021) is at least EUR 142 billion and the total cost of flood risk reduction measures planned in the 1st WFD planning cycle (2016-2021) is at least EUR 14 billion. In the absence of large-scale adaptation measures, flood damages from the combined effect of climate and socio-economic changes are projected to increase from EUR 6.9 billion/year to EUR 20.4 billion/year by the 2020s and EUR 45.9 billion/year by the 2050s.

Since 2019, some regulatory developments have taken place in relation with the WFD implementation

- Water efficiency: Regulation (EU) 2020/741 on minimum requirements for water reuse in agriculture was adopted in 2020. However, it has only partially compensated for the lack of attention paid to quantitative aspects in the WFD compared to quality issues. Many developments are underway to promote water efficiency in industry and households.

- Soil protection: After the withdrawal of the proposal for a solid framework directive in 2014, the European Commission came back in 2021 with a Soil Strategy for 2030 – COM(2021) 699, which sets out a framework and concrete measures to protect and restore soils. The recycling of organic matter such as compost, digestate, sewage sludge, processed manure and other agricultural residues is a key issue: on the one hand it serves as an organic fertilizer, helps to replenish depleted soil carbon pools and improves water retention capacity and soil structure, but on the other hand it is a major source of pollutants. This is a critical issue for water utilities, as sludge treatment is a major cost driver. A public consultation on the possible Soil Health Act has been organized in 2022 (link).

- Urban wastewater treatment: An agreementon a revised Directive was reached in April 2024 between the Concilium on the European Parliament (text approved by the EP). Main changes are:

- Mandatory application of quaternary treatment for all plants of over 10.000 population equivalent by 2045.

- Extended Producer Responsibility scheme applicable to the pharmaceutical and the cosmetic industries will have to support at least 80% of the quaternary treatment costs.

- 100 % GHG emission reduction by 2045 by promoting the use of renewable energy at the treatment plants

- Monitoring pollutant of emerging concern (watch list)

- Strengthened measures to promote water reuse

When the new Commission takes office, it will face a fundamental question: If the WFD is fit for purpose, why is it that only 40% of water bodies are in good ecological status by the time the third planning cycle is being implemented? Diffuse sources of pollution (agriculture, urban runoff, atmospheric deposition, mining activities, etc.) clearly appear to be a major hurdle. In addition, the effects of climate change are becoming more acute. This leads to uncertainties about future water demand and availability, as well as exposure to water-related risks, as illustrated by the recent EEA report (link). However this is only part of the explanation.

A new impetus is needed to stimulate additional investment in the water sector. At present, the only sources of funding are public budgets and revenues from water utilities. This needs to be broadened, given that water investments generate a mix of public and private benefits. However, these benefits are not easily monetized, which undermines the achievement of clearly defined revenue streams associated with investments. In addition to pricing policies (e.g. for ecosystem services), offset markets (which allow actors to buy credits to offset their own emissions or negative environmental impacts) increasingly appear to be another tool to translate the value of water-related investments into revenue streams.

Finally, one can ask whether the WFD was ambitious enough in terms of integration with other sectors. The challenge is to do this without adding further administrative complexity. A recent study from the OCDE (link) has also argued for sequencing multiple projects along coherent investment pathways to maximize co-benefits and reduce negative externalities.