In March 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly adopted a resolution for the development of an “international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment“. The resolution calls for attention to product design, environmentally sound waste management, efficient use of resources and circular economy approaches. According to its mandate, this process is expected to deliver a proposal for a global treaty at the fifth Intergovernmental Negotiating Committing (INC-5) in Busan, Republic of Korea, from 25 November to 1 December 2024.

INC-4 took place in Ottawa from 23 to 29 April with 2,500 delegates participating in 5 working groups. As Systemiq put it in a briefing note for negotiators (link), the discussions can be grouped around 2 key variables: the scope of the treaty and the need for coordination.

A. SCOPE OF THE TREATY

This point ranges from comprehensive strategies covering the entire life cycle of plastics to those with a more focused approach focusing on waste management only. A life-cycle approach is likely to be more effective, but also more cumbersome to implement. It may also face resistance from plastic producers. The chart below summarises the main issues at stake along the value chain.

- Climate change: Today, about 4-8% of the world’s annual oil consumption is linked to plastics (source: World Economic Forum). If this reliance on plastics continues, plastics will account for 20% of oil consumption by 2050. Significant additional action is needed to bring the plastics system in line with the Paris Agreement.

- Plastic use: 50% consists of plastic packaging, 30% comes from construction, industrial and agricultural plastic waste, while the remaining waste comes from electronic and electrical waste (WEEE), textiles and consumer products.

- Research efforts have opened up promising prospects for biodegradable and compostable plastics as alternatives to conventional plastics for specific applications.

- Collection service: this is often neglected. Plastic recycling can only takes at a large scale if a segregated collection is organised by waste operators with the support of local stakeholders. This requires significant engagement efforts and must be supported by economic incentives.

- Sorting equipment: thanks to sensor technology and artificial intelligence, sorting equipment performs much better with Commingled waste streams. It alleviates the waste collection burden and ensure a reliable supply to the recycling industry.

- Recycling technology: Intensive research is underway to develop circular value chains for plastic waste according to its origin and composition. This will lead to additional product requirements to be included in the regulatory framework.

B. THE NEED FOR COORDINATION

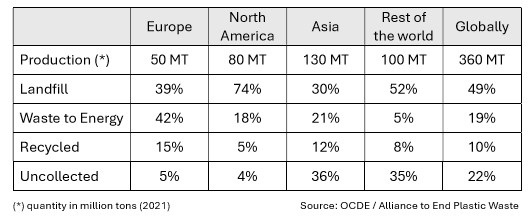

The level of coordination required to achieve the Treaty’s objective is questioned among Member States. Should the UN agree on legally binding global rules and targets, or should it promote approaches that favour national action guided by non-binding targets and guidelines? The first option implies a unified commitment to ambitious, legally binding targets and policies aimed at achieving significant reductions in plastic pollution on a global scale. On the other hand, a more decentralised approach favouring national actions based on non-binding targets may allow for flexibility, but could also lead to different levels of commitment and effectiveness. Some of the issues are related to international trade and others to the local context. The treaty will also need to address regional differences in the collection and treatment of plastic waste, as illustrated in the table below:

Considering those differences, tailoring strategies to national circumstances, infrastructure capacities and resources, appears to be a sensible approach (see the Plastic Waste Management Framework proposed by the Allaince to End Plastic Wastes). It should also be stressed that centralised coordination would be a demanding task and would require a lot of resources to ensure proper monitoring and reporting.

C. FINANCING

In general, low and middle income countries (LMICs) lack adequate treatment capacity, while municipal solid waste already accounts for 10-20% of local authority budgets. The financing gap needs to be addressed in one way or another. Financing instruments that have proved effective in developed countries (collection fees, extended producer responsibility) cannot be considered for the near future in developing countries because the fundamentals are not yet in place. Alternative financing instruments should be considered during the transition period, such as

- Carbon credit: it can be compared to carbon credit (meaning a transferable unit representing a specific quantity of plastic waste that has been collected from the environment and subsequently recycled or safely disposed. However it proves to be much more difficult to implement in practice since local context prevails. In addition plastic waste can hardly be dissociated from other municipal waste (see the GIZ position paper)

- Carbon fee: A levy would be collected at the start of the value chain when plastics are produced. This levy might be modulated according to the type of plastic. A transfer mechanism to developing countries would have to be put in place (see the discussion paper prepared by the Minderoo Foundation).

- Cash from trash schemes: These are used to ensure income for waste collectors according to the value of the materials collected and are not limited to plastics. This is an effective way of bringing the informal sector into the system.

D. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this treaty is an excellent example of the ability and added value of the United Nations to develop a multilateral approach to a global problem. There are many conflicting interests and regional differences. Consensus will not be enough to move forward. The treaty should inject new dynamism into the system and unlock new business opportunities, benefiting all member states in a fair and equitable way. This would be a historic breakthrough for the circular economy.